IT’S ABOUT ART, MUSIC & LITERATURE

KRAFTWERK

THE ELECTRONIC–MUSIC PIONEERS

In the annals of rock music, acrimonious break–ups have been attributed to rock’n’roll excess, irreconcilable artistic differences and, of course, the lure of a solo career. But only one band can claim to have had its existence threatened by the bicycle.

Triad Radio [Chicago, 1975]

“We Are European Citizens with German Passport.”

Die Roboter 1978

Music Non Stop 1991

Live 1978

BBC2 Documentary 2009

The German electronic–music pioneers Kraftwerk harbour an obsession with cycling that goes back more than 25 years. A harmless hobby that developed into a major inspiration, the sport led to the band’s partial disintegration and a 17–year creative hiatus. When they finally broke their silence in 2003, it was with Tour de France Soundtracks, a musical exploration of the joys of being in the saddle.

During their 36–year career, the band have composed entire albums on the theme of the German motorway system and rail travel, works that have influenced the course of modern music — in 2004, the electronic Beatles were ranked No 7 in a poll of “bands that changed the world”, ahead of The Rolling Stones, The Who and The Velvet Underground. Commercial success arrived in 1974 with their fourth album, Autobahn, a synthesised paean to the joys of motorway travel and the first of five albums representing Kraftwerk’s golden period. On successive releases, the founder members Ralf Hütter and Florian Schneider, aided by Karl Bartos and Wolfgang Flür, developed the band’s interest in the interaction between man, machine and nature, producing music that celebrated the advances of modern technology and slyly hymned the increasingly alienated nature of human experience.

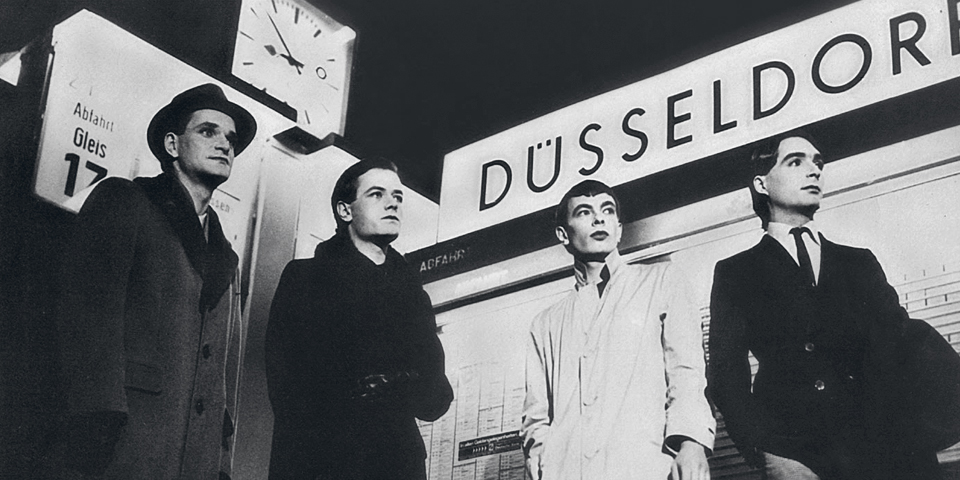

Over time, the band members, too, seemed to become less human, locking themselves away in Kling Klang, the mysterious Düsseldorf bunker that houses their studio headquarters but has no telephone or fax and returns all mail unopened. The musicians have not posed for a photo since 1978, and the focus of their live performances is their robot doppelgangers. There is minimal interaction — at their last London gig they uttered just two words — “Gute Nacht.”

It was just after the release of Computer World, in 1981, that Hütter and Schneider took up cycling, they encouraged their bandmates to join in and formed their own club, Radsportgruppe Schneider. Hütter took his new–found pastime particularly seriously, completing the classic and challenging courses of the Tour de France and the Giro d’Italia and following the big races around the world as a spectator. At the height of his obsession, he would jump off the tour bus and cycle the last 150km into the town where the band were scheduled to perform next.

It was only a matter of time before cycling made its imprint on Kraftwerk’s music. The bicycle, with its inability to travel backwards, was a perfect symbol for the band’s retro–futurist ideals. Hütter says there are many similarities between music and cycling — “speed, balance, a certain freedom of spirit, keeping in shape, technological and technical perfection, aerodynamics.”

In 1983, Kraftwerk released the Tour de France EP, inspired by the greatest cycling event in the world. “The bicycle is already a musical instrument on its own. The noise of the bicycle chain, the pedal and gear mechanism, the breathing of the cyclist, we have incorporated all this into the Kraftwerk sound”, Hütter announced. In the same year, he suffered serious head injuries in a cycling accident near the Rhine Dam [he wasn’t wearing a helmet], which left him in a coma for two days. His first words on waking were, reportedly, “Where’s my bike?” As he convalesced, work on a Tour de France LP was shelved.

This rocky period — during which Hütter also suffered a heart attack, allegedly brought on by excessive caffeine consumption — eventually bore fruit in the shape of 1986’s Electric Café, an album generally considered to be lacklustre. Its release marked the beginning of Kraftwerk’s protracted break from the limelight. During this time, the percussionists Flür and Bartos left the band, frustrated at the slow pace of work and concerned that cycling was eclipsing the music–making. “Every day, we would meet and have dinner. Ralf always talked about how he rode 200km that day. That would bore me to death”, Bartos recalled. The fact that Hütter gave an interview to a magazine in which he refused to speak about anything other than his collection of racing bikes gives credence to Bartos’s grievances.

The centenary of the Tour de France in 2003 appeared to shake the band out of creative torpor. Work was restarted on a full–length Tour de France album, using the EP, by then 20 years old, as the starting–point. Typically, the band’s perfectionist, painstaking approach resulted in the album’s release missing the 100th birthday of the great race. Tour de France Soundtracks proved a worthy tribute nevertheless, with sound effects including a French–accented vocoder, whirring chains, beating hearts and panting. “We took my heartbeat, and worked this into a kind of beats per minute, and some kind of drum beat”, explains Hütter.

“Cycling is the man–machine”, he enthuses. “It’s about dynamics, continuing straight ahead, forwards, no stopping. He who stops falls over. Always forward.”